Amidst the Pandemic, Murders Skyrocket

Source: German Lopez / Vox, Jeff Asher

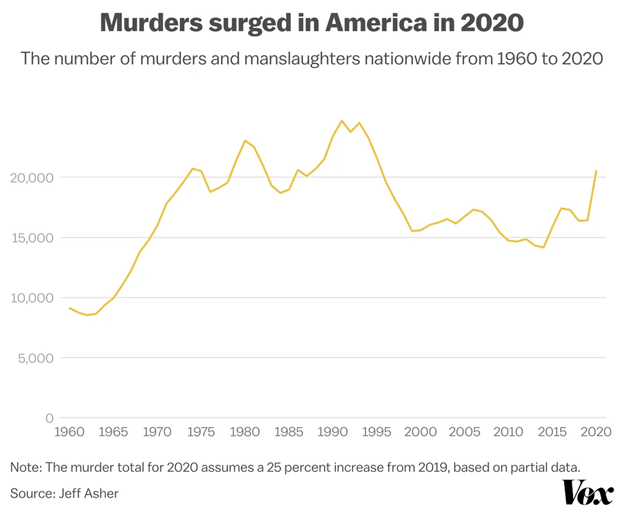

2020 saw a historic spike in homicides, threatening to erase decades of steady progress against murders and violent crime.

The three most rigorous analyses conducted to date found homicides increased by between 25 and 37 percent in 2020 compared with 2019 (preliminary data from some cities in 2021 suggests these elevated rates have persisted). Even just a 25 percent increase is twice as large as the greatest annual increase in homicides since recording began in the 1960s.

Though murders have spiked everywhere, the carnage has been especially severe in cities: murders were up 40 percent in Philadelphia, 50 percent in Chicago, 80 percent in Minneapolis, and 44 percent in New York City––long seen as a poster-child for declining crime. They’ve also disproportionately impacted specific high-poverty communities: in Chicago, for instance, homicides are concentrated in just eight percent of the city’s census tracts.

1. What specific factors have driven the spike in murders?

Although there is still much uncertainty among experts, there are three leading theories:

First, many attribute the violence to disruptions caused by the pandemic. Max Kasputin, an Assistant Professor at Cornell, explains that COVID “disrupted a whole host of institutions that act as a first line against gun violence.” Social programs like summer jobs programs and urban renewal initiatives have been shown to reduce isolation, idleness, and as a result, violence; Princeton Professor Patrick Sharkey further argues that when these programs, as well as schools, libraries, and other community spaces close, it can create feelings of widespread alienation that can turn into aggression.

Second, some researchers point to the recent break in trust between police and civilians. Homicides typically spike in areas following high-profile cases of police brutality—this happened in Ferguson after the killing of Michael Brown (which may have contributed to a nationwide 11% increase in homicides in 2015), in Baltimore after the killing of Freddie Gray, and now, perhaps, around the country after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others. This phenomenon occurs not necessarily because officers respond to fewer calls with greater caution. Rather, when trust erodes due to incidents and the subsequent backlash, police morale sinks, which may make officers more reluctant to build relationships with communities, investigate difficult cases, and engage in other forms of “proactive policing” that may prevent crime. In addition, distrustful victims and witnesses become less willing to report incidents, which can lead to “street justice” that makes matters worse.

Third, others look to heightened gun sales. Buoyed by lockdowns, unrest over the summer, and the election of Joe Biden, gun sales shot up a historic 60 percent in 2020, and an estimated 8.4 million Americans bought their first gun. The academic research is robust: even assuming violent crime does not increase, more guns mean more gun deaths. When firearms are present, confrontations that would otherwise be non-lethal turn deadly (suicides generally spike as well). Preliminary findings suggest this time is no different.

2. Is this spike likely to continue?

First, it’s important to note that while it’s certainly bad, the situation may not be quite as grim as it might seem. Many other types of crime, both violent and non-violent, have by all indications stayed relatively steady even as homicides have risen. Furthermore, murders are rising from a low baseline: there were 462 murders in NYC in 2020, a 44 percent jump from 2019 but nonetheless far below the 1995 figure of 1,177. There have also been blips in the murder rate before, like in 2015-2016 and 2005-2006, for instance. What’s more, though we should not rely upon this, as the pandemic comes to an end and life returns to normal, the spike may naturally fizzle. That said, pervasive fear can cause more people to carry weapons and interpret uncertainty as hostility, which can in turn exacerbate the rise in crime.

Second, going forward, we should consider a strategy of “focused deterrence.” This approach targets the most vulnerable, providing them with jobs and schooling to reduce the disaffection that can turn into aggression. It was linked to a 50 percent decrease in homicides in Oakland, CA from 2012 to 2017, is credited with the 1990s “Boston miracle” in which homicides dropped 79 percent, and was endorsed by two separate literature reviews.

Nevertheless, there are no easy answers. But overgeneralized blanket criticisms demonizing all officers are not helpful and make reasonable criticism less effective. Even in the “successful” years prior to the pandemic, high levels of incarceration remained a problem. The solution is any number of possible reforms including addressing the racism that still plays a role in too many tragedies, de-militarizing departments, and training officers in the use of non-lethal tactics—not demonizing every officer. We can transform policing (which might actually cost more money rather than less) without belittling police.

In the meantime, we must pay attention. Ignoring this epidemic of violence will do nothing to solve it, and recognizing the gravity of the problem is only the first step.