From Chile to Mexico, 2021 has been filled with major elections across Latin America. While the voters have weighed in on referendums, filled seats for legislatures, and selected heads of state, the elections have shared a key characteristic: extremism tends to be on the ballot, and it often does well.

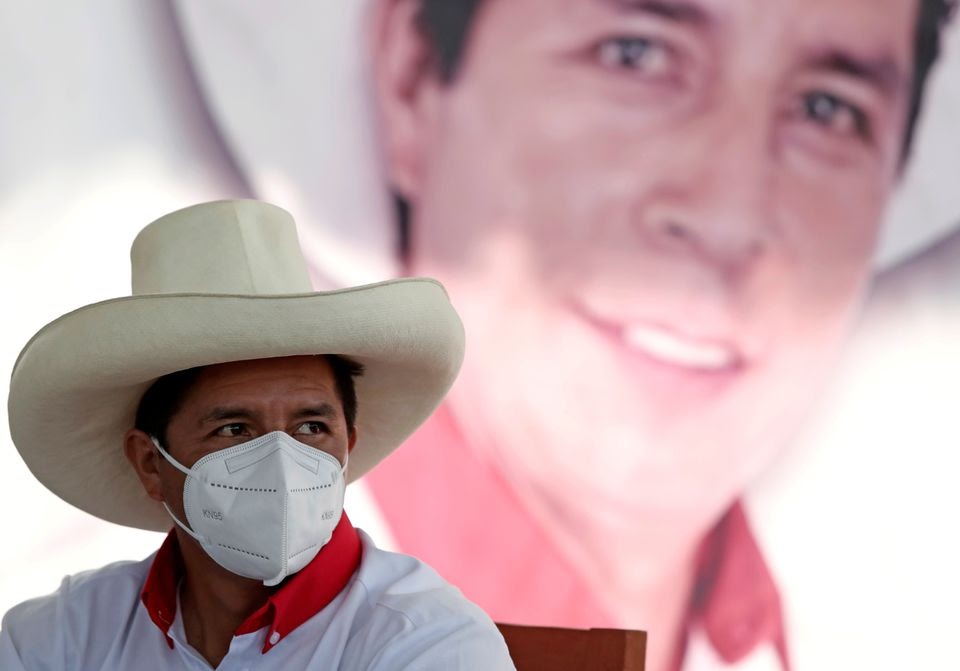

Latin America is hardly the only region struggling with extremism in democratic elections, but it does seem to be even more affected than most. In Peru’s presidential election in June, voters chose between the daughter of an imprisoned former dictator who led death squads against his citizens and a socialist who wanted to rewrite the constitution, threatened to dissolve Congress, and hoped to nationalize industry. The socialist, Pedro Castillo, is now the president of Peru.

Just this past month, elections were held in Chile, Honduras, Argentina, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. In Chile, a far-right candidate, Jose Antonio Kast, finished on top with 28 percent of the vote, sending him to a runoff election with his leftist opponent, Gabriel Boric. Kast’s commitment to democracy is dubious, and, leaning into anti-immigrant nativism, he has promised to dig a trench to keep migrants out. Last year, voters approved a referendum to hold a constitutional convention, so Chile is bound for radical change in any case.

In Honduras, far-left candidate Xiomara Castro won the presidency last week and promised to rewrite Honduras’ 1982 constitution immediately after taking power. She’s the wife of former president Manuel Zelaya, who also tried to change the constitution before being deposed in a widely-condemned military coup.

In Venezuela and Nicaragua, the entrenched dictatorships of Nicolás Maduro and Daniel Ortega precluded the possibility of any real elections, but the very fact that they bothered to hold sham elections shows how important the trappings of democracy are even in unfree countries. Both countries were also democracies relatively recently, and the current dictatorships were only able to take power because they were voted in democratically (in Maduro’s case, his predecessor Hugo Chávez won election then transferred power to him). Any election can be a democracy’s last, and candidates like these seem intent on making it that way.

Why is extremism so appealing?

As a cascade of crises strike Latin American countries, voters are increasingly demanding radical reponses. In Peru, the moderate establishment parties floundered as voters railed against rising inequality and massive levels of corruption that persisted over decades. Honduras struggles through uncontrolled violence and economic ruin, and Chilean politics is being destabilized by the public’s backlash to Venezuelan migrants, among other crises. Venezuelan migrants are only arriving, of course, because 23 years ago the public gambled on a young Hugo Chávez to rewrite the constitution and cure long-unaddressed issues, ultimately leading to the destruction of the state. Moderation hasn’t offered an effective cure to these massive dilemmas, and in its stead, extremism is gaining ground.

Here, the political radicalism of certain Latin American countries offers a warning to Americans: if voters can’t get what they want through establishment politics, they’ll look elsewhere. Whether in far-right candidates in Chile or in far-left candidates in Peru, popular discontent favors extremists. If democracy can’t deliver meaningful progress to voters’ lives, then its chances of survival suffer terribly.