Why the world’s largest dictatorship keeps calling itself a model democracy

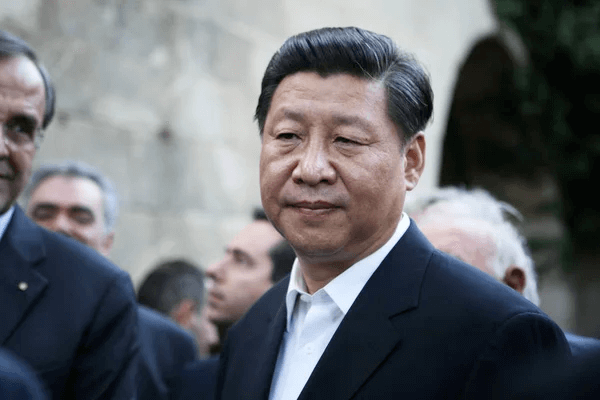

The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is underway in Beijing this week, broadcasting China’s ambitions for the future. The congress meets every five years and coincides with presidential terms, so Xi Jinping, having served his two five-year stints, should be welcoming a successor. But in 2018, officials undid term limits, paving the way for him to rule for life.

Xi enters his third term as the most powerful ruler in China since Mao, and the most globally significant ruler in Chinese history. He is defining an era of unprecedented change for China while purging rivals, dismantling the systems put in place to guide succession, and upending what existed of Chinese meritocracy. After ten years in power, Xi’s control of China is stronger than ever.

Americans might be surprised then, that in Xi’s nearly two-hour speech opening the conference, he referenced Chinese “democracy” 28 times. Laying out China’s development goals for the next five and fifteen years, Xi said it would be a priority to “improve the system for whole-process people’s democracy.” He later explained that “whole-process people’s democracy is the defining feature of socialist democracy; it is democracy in its broadest, most genuine, and most effective form.”

China is most certainly not a democracy, but this talking point is a popular one. In February, China and Russia released a joint statement describing themselves as “world powers with rich cultural and historical heritage [that] have long-standing traditions of democracy.”

Since democracy is in retreat around the world, it’s easy to forget just how thoroughly it won the battle for hearts and minds. I mean, it really, really won. Any state that wants to appear civil and modern must be democratic. It is the only legitimate form of government in the 21st century, and autocrats took notice. But this victory of democracy also poses a risk––if dictatorships are trying to redefine the term to suit them, do we all risk losing sense of its meaning?

The Triumph of Democracy

The democratic revolution unleashed by the United States and France in the 18th century engulfed the world. That governments should form from the consent of the governed who collectively decide their own future is now indisputable. Every other justification for rule melted under the tide of democracy, and seemingly no setback could stop it for long. The idea of democracy took on a life of its own.

Democracy grew from a historical oddity in the United States into the hallmark of modernity. Kings, emperors, and sultans were abandoned in favor of presidents and prime ministers. Democracy and modernity became inseparable. China, like all countries, was forced to adapt.

The Chinese Communist Party’s use of the term democracy is not new. In 1940, Mao wrote On New Democracy, where he argued that “the Chinese revolution must go through two stages, first, the democratic revolution, and second, the socialist revolution.” Mao explained that “this new-democratic republic will be different from the old European-American form of capitalist republic under bourgeois dictatorship, which is the old democratic form and already out of date.” By that, he meant that democracy would be an adornment to his dictatorship. It was a label that conferred popular legitimacy on the communist regime, not the supposedly outdated system of elections, checks and balances, and liberties that defines the term to those of us in the West.

By the new millennium, China was an emerging great power home to more than one billion people. The government no longer just had its citizens to contend with, but was also increasingly concerned with its international image. Touting Chinese democracy took on a dual purpose: to defend the CCP’s legitimacy at home and to assert it as a forward-thinking, modern government abroad.

Redefining Democracy

In 2007 at the 17th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party officials presented a white paper on China’s political party system introducing “socialist democracy” as the defining feature of the Chinese system. It is supposedly “the combination of democratic election and democratic consultation,” though elections were incapable of actually affecting CCP rule. Chinese socialist democracy relied on the idea that the communist party was acting on behalf of the people, as “The CPC’s leadership and rule is to lead and support the people to be the masters of their country.”

As Xi took power in 2012, the claim that China is a democracy took on a new form as “whole-process democracy.” It emphasized the positive outcomes of the system rather than the process of governing, and compares the stability of a one-party state to the unpredictability of Western democracy. At the same time, China became increasingly assertive that its form of democracy was not only equally legitimate to Western democracy, but superior.

While the Biden Administration was about to begin its Summit for Democracy in December of 2021, China released a sprawling document on its thriving democracy and another on the failures of American democracy. China concedes that humanity has a “universal desire for democracy,” but “democracy is rich in form, and there are many ways to achieve it.” Rather than worrying about the systems and processes which define democratic rule, countries should “develop forms of democracy suited to their own modernization process.” In other words, countries should decide for themselves what democracy means.

In an age of democracy, dictators recognize that being seen for what they are is a threat to their power. That’s why in February Russia and China issued a joint statement demanding that “the advocacy of democracy and human rights must not be used to put pressure on other countries.” If we are all democracies, then Western ones have no standing to criticize the abuses of foreign regimes.

Troublingly, the rise of dictatorships loudly cheering their “democracies” coincides with a weakening in Western democracies’ own understanding of the term. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán proudly defends his “illiberal democracy,” which the European Parliament voted last month to recognize as an “electoral autocracy.” Nevertheless, CPAC traveled to Hungary to encourage Orbán and Sen. Ron Johnson described him as an inspiration for the US.

The black-and-white struggle between democracy and autocracy is at risk of blurring into a confused gray area where autocracies call themselves democracies and once democratic states drift toward authoritarianism. If we continue down this path, China and Russia will have achieved their stated wish of making it impossible to “draw dividing lines based on the grounds of ideology.” No country will be free or unfree, but merely different.

The trouble for dictators is that until democracy is replaced as the only legitimate system of government, they will never truly be safe. Look at Iran, where after more than 40 years of oppression at the hands of the Islamic regime, women are reasserting their fundamental right to make decisions for themselves. Freedom isn’t easy to unlearn, and even destroying the definition of democracy won’t do away with individuals’ basic interest in having a say in their futures.