By Edward Radzivilovskiy

Moderation seems to be getting a bad rap these days. In an increasingly polarized political climate, compromise is often seen as cowardly. Taking time to think about an issue before giving an answer is sometimes interpreted as being indecisive. But what does “moderation” really mean? Some call it selling out but is this actually true?

The concept of moderation (or temperance) can be traced back to the ancient world. The Greeks included it among the Four Cardinal Virtues (the others being Justice, Wisdom, and Courage), but moderation was considered to be the most important due to its regulatory role. For example, too little courage was considered cowardice. Too much courage was considered recklessness. Moderation helped you find the right balance.

Moderation is not necessarily an ideological stance, but an intellectual attitude that enables restraint and reflection. And you’re not born with moderation; you acquire it over time—as you would with any other skill. Without this principle of moderation, debates turn into reality TV as emotions overwhelm facts and the loudest voice wins. Beyond politics, without the principle of moderation, the mind lacks self-discipline. Our impulses, desires, immediate wants and needs, overwhelm our filter mechanisms. Not only do we make bad decisions, but our decision-making capacity in-and-of itself erodes over time.

In our society today, do you see the kinds of moderation described above? Do you see moderate political movements? Do you see moderate leaders? Unfortunately not. Increasingly, our political tribes do not reflect moderation. They reflect the extremes, kowtowing to the loudest elements in society rather than the more reasonable ones. Though social movements are frequently driven by an understandable anger over injustice, they could be more effective if tempered by an impulse of moderation that broadens the tent and allows for compromise between different groups. Meanwhile, our leaders are all too willing to appeal to fear and division, while loudly condemning the type of compromise that might actually lead to progress and greater national unity.

Now, this doesn’t mean that moderation should lead us to compromise on our values or stop us from fighting for what is right. It does, however, mean that we should, when possible, explore making significant reforms without undermining those institutions that allow groups in society to resolve conflicts peacefully.

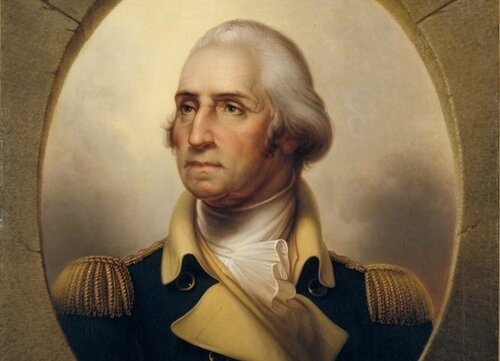

Thomas Jefferson singled out George Washington’s moderation as the most important value that allowed America to succeed in its early days, praising Washington in a letter: “[T]he moderation and virtue of a single character has probably prevented this revolution from being closed as most others have been by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish.” Indeed, it was Washington’s restraint and reflection that ensured a transition from a Revolution to a Republic. He shifted from an unyielding opposition to the British to figuring out how to bring disparate states into a single union when there was no common enemy to unite against. This form of consensus building required the very sort of compromise that is all too frequently demonized in DC today.

And Washington understood the importance of not letting emotions overwhelm facts, advising his nephew Bushrod to prioritize listening over speaking: “Rise but seldom….Never be agitated by more than a decent warmth, and offer your sentiments with modest diffidence—opinions thus given, are listened to with more attention than when delivered in a dictatorial style.”

Part of the problem in today’s heated environment is our inability to view politics from a Washingtonian viewpoint—that is, objectively. Indeed, moderation requires a level of detachment. Just as the ideal debate moderator detaches from personal preferences and political leanings in order to safeguard a fair debate, a moderate detaches himself from knee-jerk reactions. Indeed, instead of accepting or rejecting an idea immediately, we should allow ourselves to play Devil’s Advocate and consider it from all possible angles. Moderation deepens our ability to think by deliberately slowing down how we digest information.

The success of our democracy depends—at least in part—on the extent to which we embrace the virtue of moderation. We have to step back and ask: is a society in which we are all screaming at one another really what we want our democracy to look like? Just as we must recommit ourselves to values underpinning our Constitution such as the Rule of Law, Popular Sovereignty, and Separation of Powers, we must also recommit ourselves to the important character trait of moderation.

Edward Radzivilovskiy is Program Manager at RDI. Contact him at edward@rdi.org