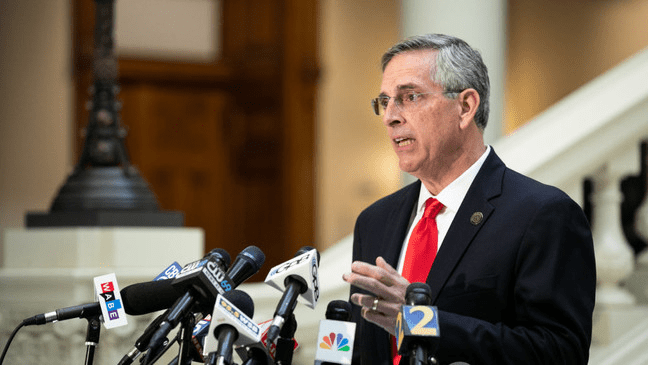

In early January 2021, Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger resisted intense pressure from then-President Trump to change Georgia’s vote count in the President’s favor. In refusing to accept unsubstantiated claims of election fraud, Raffensperger, a Republican, drew praise from Democrats and pro-democracy groups across the country. But for many of his fellow Republicans, Raffensperger’s refusal was a bridge too far. Now, the Georgia state legislature has passed a law to limit the power of Raffensperger’s office moving forward.

The law, signed by Governor Kemp last Thursday, initially garnered attention in the national media for its provisions to limit absentee voting, a move critics argued would make it harder for Democrats and minorities to vote. Notably, Raffensperger supported many of these measures, arguing that they were necessary to improve election security. He was probably not as pleased, however, with a lesser-known provision of the law that weakened the power of his own office.

The legislation removed the Secretary of State from the state election board, the body in charge of formulating the rules that govern state elections and overseeing investigations into potential electoral fraud. The new law places the board chiefly under the control of the Republican state legislature, who will now appoint a majority (three out of five) of the board’s members. The law also gives the Election Board increased power to fire and replace appointed county election officials.

1. What does this law mean in practice?

In a state where elections are administered on a county-by-county level, these provisions could have far-reaching consequences. The Election Board will now have the power to replace up to four county “elections superintendents,” who are responsible for certifying county election results, changing polling places, and hearing challenges to voter eligibility. By replacing elections superintendents in heavily democratic areas like Fulton County, the Election Board could make voting in these areas more difficult, or even attempt to prevent or alter the certification of votes. In 2020, this might have been enough to flip the Democrats’ razor-thin margin of victory.

Opponents of the law similarly point to the legislation as a clear example of retaliation against an official who refused to accept the narrative of a “stolen election.” Since publicizing his infamous phone call with Trump, Raffensperger has been edged out of the Georgia Republican Party, failing to be chosen as a delegate for his county’s Republican Convention. Now, he is facing a primary challenge by a Trump-backed state representative in his bid for re-election in 2022. Speaking to Politico, Jay Williams, a Republican strategist, was blunt about Raffensperger’s political future: “He’s toast,” Williams said.

What’s happened to Raffensperger may serve as a warning to future election officials under pressure to change results, dissuading them from taking a principled stance that could end their political careers. Future Secretaries of State—who are still responsible for certifying state election results—may adhere more closely to party lines, even when that means breaking their oath of office. Meanwhile, county-level officials may increasingly be replaced with partisans. This is an ominous sign for the future of American democracy and should be a significant concern across party lines.

2. How do we protect the independence of elections officials?

Georgia isn’t the only state where the legislature is attempting to seize power from elections officials. Similar laws have been introduced in Arizona, Iowa, Michigan, Kansas, and New Jersey. Though some of these laws—particularly in states like New Jersey and Michigan with Democratic governors—will not pass, the trend is nonetheless deeply concerning.

The 2020 election hinged upon the integrity of a courageous group of officials who stood up for free and fair elections in key swing states. The independence of election administrators is now under assault nationwide, threatening our very democracy.

Urgent reforms are necessary to protect us from this ongoing threat moving forward. Bills to expand voting rights will help, but may not be enough to prevent states from simply discarding constituents’ votes. Federal legislation must be introduced to mandate that the true results of elections be certified unless there is clear and credible evidence of fraud.

In the long term, an end to the gerrymandering that creates hyper-partisan state legislatures and a reconsideration of the Electoral College system are other potential legislative routes towards countering partisan attempts to influence state election administration.

If we fail to act, a small number of state officials may increasingly have the power to influence national elections. Unlike Raffensperger, many of them will be unwilling or unable to resist partisan pressure.