Putin’s invasion of Ukraine remade German policy––sort of

The German government would like you to know it’s changed.

On February 27, three days after Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, Chancellor Olaf Scholz declared it a Zeitenwende––a watershed moment––for German policy. No more Russian oil pipelines. No more believing that lucrative deals could turn rivals into friends. No more emaciated Bundeswehr, barely able to qualify as a functioning army.

The shift was long overdue. The German political establishment spent decades operating on the premise that borders were fixed, war had become obsolete, and Russia wouldn’t threaten European security after the Cold War. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine destroyed that dream and German credibility alongside it.

Now, almost a year on from the Zeitenwende, Germany has licked its wounds and launched a PR campaign, asserting itself as a global leader who’s learned its lesson. For the January/February edition of Foreign Affairs, Scholz published an expansive 5,000-word piece on “The Global Zeitenwende: How to Avoid a New Cold War in a Multipolar Era,” outlining his worldview and Germany’s guiding role in it. Last month the German ambassador to the US, Emily Haber, took to the opinion section of the Washington Post to explain Germany’s remaking:

“We ignored warning signs to the contrary, and we failed to take criticism from our allies and partners as seriously as we should have, especially on the geopolitical implications of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline.

All of this is now over, and it is amazing to observe just ‘how over’ it really is. Our old strategic axiom of ‘Wandel durch Handel’ (‘change through trade’) is dead.”

This is welcome news for democracies the world over. Germany’s policies have split allied countries on contentious issues, funded the Russian war machine, and undermined European security. Still, almost a year later the Zeitenwende has proven to be a mixed bag––some positive changes and promises kept, yet some threats left unaddressed and commitments broken. In the coming months, Germany’s choices will determine just how significant of a watershed moment the Russian invasion really was.

The Good

The German government deserves credit for reversing long-held policies regarding trade and weapons exports.

First, the German government is no longer claiming that money is politically neutral and business deals with foreign autocrats have no relation to politics. It’s easy to understate just how major of a shift this is in German policy. The principle of change through trade––that authoritarian regimes could be made more liberal through economic engagement––was an axiom of German policy for half a century. Even after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 and continued to meddle in democracies around the world, the German government remained stubbornly committed to its policy.

Take the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. When the US imposed sanctions on the deal in 2019 for undermining European security, then-finance minister Scholz called it an infringement on German sovereignty. In the summer of 2021, Scholz campaigned for chancellor on a platform of carrying Nord Stream 2 to completion despite the fact that Putin was amassing troops around Ukraine. By December, more than 100,000 Russian soldiers surrounded Ukraine and Germany’s vice chancellor Robert Habeck said that “from a geopolitical point of view, the pipeline is a mistake.” Yet Scholz still insisted it was simply a private sector project with no relation to politics. It was only on February 22, two days before the Russian invasion, that Scholz finally revoked the pipeline’s certification. Now, Germany has committed to buying no Russian oil in 2023, despite significant price increases in the German energy market.

Second, Germany reversed its precedent of not sending weapons into active conflict zones. After initially blocking other European countries from providing German-made howitzers to Ukraine out of fear of escalation, the country has since sent its own howitzers along with anti-aircraft tanks, missiles, and rocket systems. Germany is still refusing to provide military support to Ukraine at a scale consistent with its geopolitical influence and economic heft, but the government’s progress on this front is commendable.

The Bad

The German policy revolution has not gone far enough, both in honoring the commitments laid out in February and in avoiding over-dependence on authoritarian regimes.

Reiterating his commitments from the Zeitenwende speech in February, Scholz wrote in November that “Germany will invest two percent of our gross domestic product in our defense.” Yet to understand Scholz’s commitment, you need to read the fine print. Germany will not meet the 2 percent target in 2022 or 2023. It may in 2024 and 2025, but then it will fall short again from 2026 onward after a one-time €100 billion fund runs dry.

This is hardly the shift toward an assertive Germany that the chancellor has promised. As Harvard fellow Lukas Paul Schmelter pointed out: “None of this suggests a change of era. Given the dismal state of Germany’s military, the Bundeswehr, including a lack of functioning equipment, the current steps are unlikely to measurably improve Germany’s defense capabilities. Much higher spending will have to be sustained over at least a decade just to make up for past neglect—instead, Berlin is still dragging its feet.”

And more importantly, Germany has yet to demonstrate whether the Zeitenwende represents a change in Russia policy or a fundamental shift in how the country conducts foreign policy. In regard to China especially, this is no small question.

The Divide on China

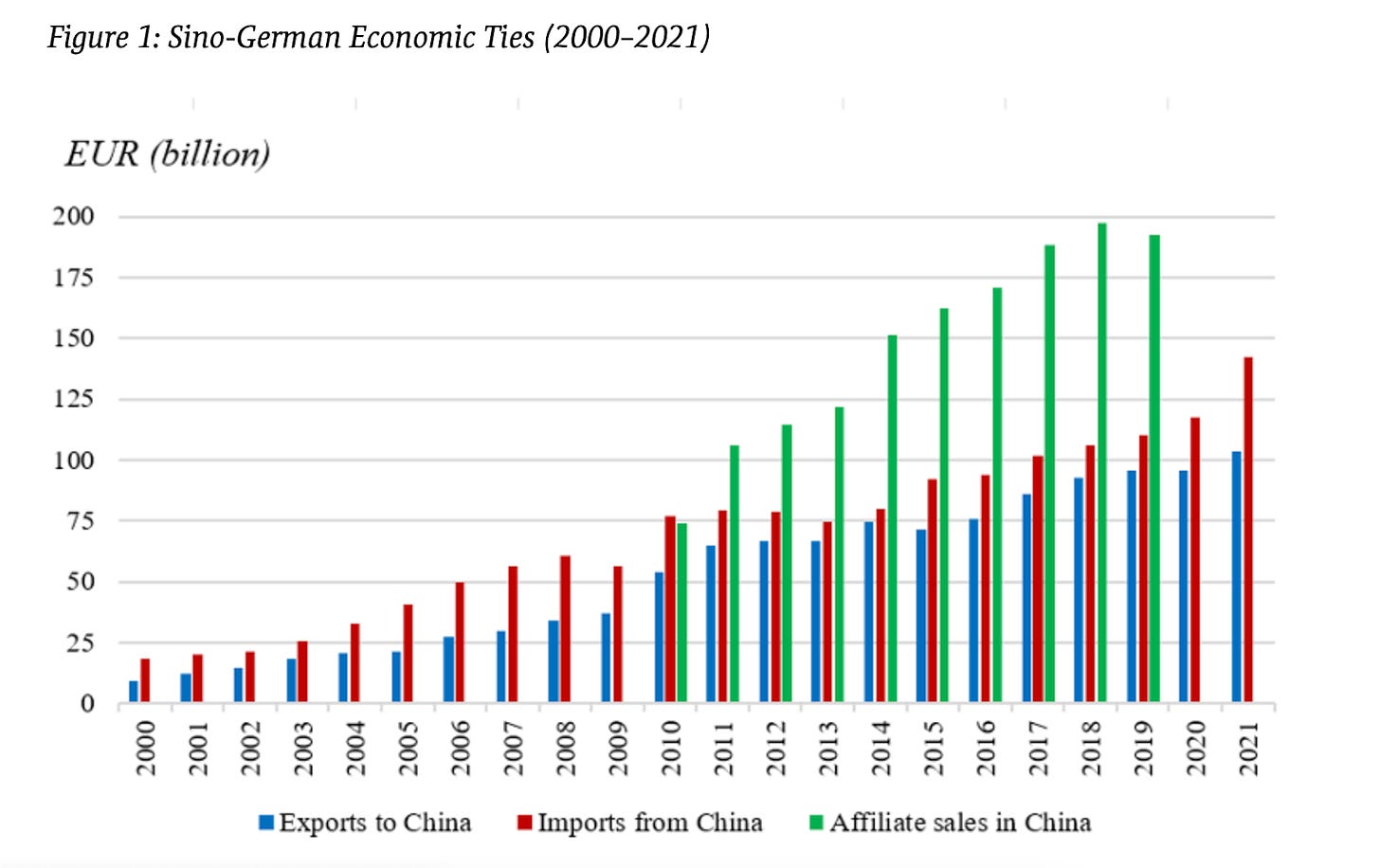

The German political leadership is split on what the Zeitenwende means for the country’s relationship with China. Over the past two decades, Chinese trade has remade the German economy, with China quickly becoming Germany’s largest trading partner. In diplomatic visits, Merkel would often travel alongside business executives, mixing trade and foreign policy. As Xi’s government drew ire for the destruction of democracy in Hong Kong, Uyghur genocide, digital surveillance and espionage, threats over Taiwan, and intellectual property theft, Merkel finally said in 2021 that “maybe initially we were rather too naive in our approach to some cooperation partnerships [with China].”

Yet where Germany should go from here remains an open debate. On one side, leaders like Scholz are pushing for a softer approach. In a Politico op-ed before a trip to Beijing in November, Scholz wrote that “where risky dependencies have developed — for important raw materials, some rare earths or certain cutting-edge technologies, for example — our businesses are now rightly putting their supply chains on a broader footing.” He made clear that Germany doesn’t “want to decouple from China, but can’t be overreliant.”

The principles Scholz articulated are more or less what everyone in Germany agrees on––it’s how to achieve them that is the problem. Skeptics like foreign minister Annalena Baerbock support a more cautious approach to China, not decoupling in the sense that entrenched trade relationships would cease. As she explained, “one-sided economic dependence exposes us to political blackmail… We must ensure that we don’t make such a mistake again, and that means that we will have to take account of this more strongly in our policy toward China.”

Meanwhile Scholz risks continuing with Merkel’s practice of pursuing trade based “on national, not European interests,” Judy Dempsey of Carnegie Europe explains. Under Merkel, German policy “was motivated by profit, not values or principles.”

The greatest potential for change rests in a new China strategy that the government ordered in 2022 and is set to be published sometime in early 2023. That document, though, is proving contentious. Foreign Minister Baerbock created a 60-page draft, yet “Scholz’s team say they would like to cut [it] in half, tone down its language, and excise several policy proposals,” according to Noah Barkin of the German Marshall Fund. Meanwhile the Chinese government is lobbying behind closed doors to get Baerbock replaced, recognizing how pivotal she is to Germany’s changing policy.

Pressure is mounting on Germany. From within, the German intelligence community is sounding the alarm that something needs to change. The German spy chief Bruno Kahl implored government officials to not be naïve about China, as they had been about Russia despite the intelligence community’s warnings. And internationally, Germany’s policy is isolating democratic allies who perceive the country as relentlessly pursuing profits at the expense of collective security. As strategic analysts Fergus Hunter and Daria Impiombato wrote for Foreign Policy, “Scholz’s Germany-first approach has confused his coalition government’s development of China policy and alienated partners in Europe and beyond.”

The continued rise of China will pose challenges to democracies that demand collective action. Troublingly, China shows little sign of breaking its “iron-clad” friendship with Russia as it develops into a military goliath. An invasion of Taiwan, something China has almost explicitly promised, risks triggering a global crisis with even larger implications for the global economy and world order than Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Unity among democracies is essential to ensure that doesn’t happen.

While Germany has shown significant progress in recognizing Putin’s regime for what it is, it remains to be seen whether or not Germany foreign policy will really be transformed. The fate of the Zeitenwende rests on the government’s China policy, and the stakes are high that German leaders get it right.