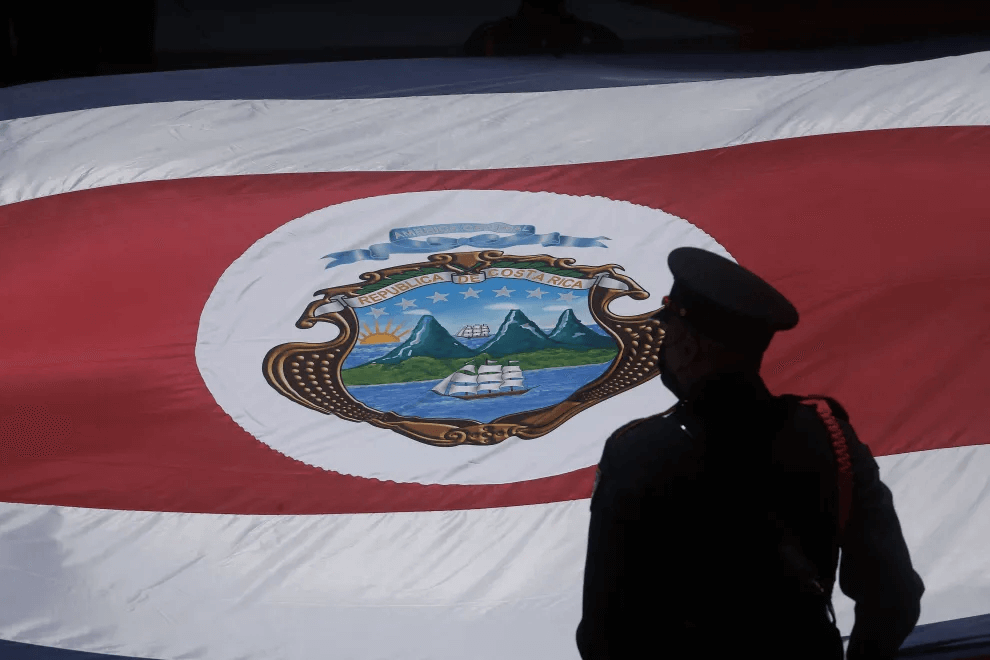

Costa Rica’s government struggles through debilitating cyberattacks by a group calling for regime change

On April 17th, Costa Rican officials in the Ministry of Finance realized they were facing a massive cyberattack, locking them out of their network. Over the following weeks, 26 other government institutions ultimately fell victim, crippling the Costa Rican government’s ability to conduct business as usual.

The effects were devastating: hospitals were forced offline, customs agents managing tens of millions of dollars worth of daily trade reverted to doing their work on pen and paper, and thousands of public sector employees stopped receiving their full pay.

Two days into the attack, the Costa Rican Chamber of Foreign Commerce estimated that it had already cost the country $125 million, and Congresswoman Gloria Navas reported that Costa Rica lost another $30 million each day afterward as the government worked to regain control of its systems.

In the midst of the crisis, a new Costa Rican government was sworn in. Outgoing President Carlos Alvarado said, “My opinion is that this attack is not a money issue, but rather looks to threaten the country’s stability in a transition point.” Upon taking office, the new president, Rodrigo Chaves, immediately declared a national emergency and then announced to his countrymen that “We are at war.”

Costa Rica wasn’t at war with another country, but with Conti, a hacking cell working out of Russia. And while Conti’s demands began with money, they didn’t stop there.

In public messages from May, Conti declared, “We are determined to overthrow the government by means of a cyber attack.” In another statement, the organization wrote “I appeal to every resident of Costa Rica, go to your government and organize rallies […] if your current government cannot stabilize the situation? maybe it’s worth changing it?”

Costa Rica may be the first country to face off with a private cyber criminal group seeking to topple the democratically-elected government. Unfortunately, it probably won’t be the last.

What is Conti?

Conti appeared in 2020 and immediately established itself as one of the largest ransomware criminal rings in the world, conducting 400 attacks that year. According to best estimates, Conti extorted somewhere between hundreds of millions and multiple billions of dollars from their victims over the past two years.

The group operates out of Russia, where it employed approximately 350 people at its peak and maintained physical office spaces near Saint Petersburg. Given the high-profile nature of their work and the massive scale of the operation, Conti couldn’t fly under the radar of Putin’s government. It didn’t need to.

Russia is the global leader in organized cybercrime, and the government is willing to turn a blind eye. Groups just have to follow a few unwritten rules, the most important of which are don’t target Russian companies and don’t damage Russian interests abroad. Beyond that, the criminal rings are free to hack, extort, leak, and steal as much as they can, and they do a lot of it. Russian hackers take in about 74 percent of all global ransomware payments.

Conti’s place in the web of Russian criminal hacking syndicates is nothing particularly special, but the attacks on Costa Rica and the organization’s call to topple the government were unprecedented.

Attack on Costa Rica

Even before the attack on Costa Rica, Conti’s leaders decided to wade into politics.

After Russian forces invaded Ukraine on February 24th, Conti released a statement. The Russia-based organization declared full support for Putin’s government and promised, “If anybody will decide to organize a cyberattack or any war activities against Russia, we are going to use our all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy.”

A few days later Conti released a second statement walking back their support for Putin, but the damage had already been done.

While Conti was a criminal ring based in Russia that had the tacit support of Putin’s government, it wasn’t a purely Russian entity. It employed foreigners, including Ukrainians, and kept a productive distance to politics.

Then, just four days after Conti expressed support for the war, the leaks began. Allegedly released by a Ukrainian who worked for Conti, 60,000 messages and files were made publicly available revealing the inner workings of the criminal syndicate.

Before, Conti existed in a delicate balance between appeasing the Russian government, holding together a workforce with conflicting political opinions, and appearing apolitical enough to avoid direct association with the Russian government. With its declaration in support of Russia’s war effort, it destroyed that. As Conti’s secrecy was undermined and its Russian ties were now explicit, companies became legally barred from even paying ransom out of risk of violating US sanctions. The for-profit crime ring had been exposed, and now it couldn’t collect after its attacks.

Nevertheless, months later, it targeted Costa Rica’s government anyway.

In this context, the hack on Costa Rica is difficult to explain. Surely, the hackers knew that it was exceedingly unlikely the Costa Rican government would pay them. Targeting governments is always a risky move, and calling for regime change along with a ransom notice seems completely insane. So what is going on?

Analysts’ theories differ, but most agree that Conti was well on its way to completely dissolving before the hack even began. Some speculate that the attack served as an advertisement for members of the group before they joined other hacking groups, while others claim that it was politically motivated to punish an American ally. Some think it provided cover for ex-Conti hackers as they moved into or established other criminal groups, while some think Conti was contracted to target Costa Rica by a client.

Whatever the cause, the result is the same: a dying criminal ring went to war with a democracy—and nearly brought the government to its knees.

The Cyber Threat to Democracies

The Free World is no stranger to dangerous cyberattacks. From 2004 to 2017, Russian state-sponsored groups meddled in 27 elections. Just last week, the heads of the FBI and MI5 gave an unusual joint address where they discussed how the Chinese government is actively undermining democracies through digital theft, manipulation, and hacking. And all the while, Russian groups similar to Conti with more direct ties to the government continue to operate. One such group, Killnet, declared “war” on 10 countries, including Ukraine and its Western allies, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Still, with Conti we have to contend with something else—the rise of unhinged groups acting independently of state orders aiming to topple governments. If a group lacking the resources and direction of a state-run operation could inflict so much damage on a country, a coordinated attack would be many times worse.

Congress recognizes this threat isn’t going away, and in March passed a massive budget increase for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). That’s a good thing, but it won’t fix the root problem. The Washington Post convened a group of cybersecurity experts, and most agreed that the United States is “just as vulnerable to cyberattacks or even more vulnerable today than it was five years ago.” While we’re taking steps to protect ourselves, hackers and foreign governments are doing more to stay ahead of us.

The attack on Costa Rica and our own experience with last year’s Colonial Pipeline shutdown should serve as a wake-up call. The cyber threat is rising, democracies are playing defense, and hacking groups aren’t afraid to destabilize entire countries.

As Sergey Shykevich, a cybersecurity expert at Check Point told Wired, “Conti put their stamp on a new era in ransomware. They proved and showed that a cybercrime group can do country extortion.”