After years of lackluster election results, the Far Right is establishing itself as a formidable force in European politics again with no sign of stopping.

The Far Right is on a tear in Europe.

Over the past year, voters across the continent have elevated far-right, populist parties into some of the most important offices in Europe. Once shut out from parliamentary politics, these parties are joining ruling coalition governments and watching as centrist parties adopt their ideas.

Just this week, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni of the far-right Brothers of Italy party hosted representatives from more than 20 Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, the IMF, and the UN at the first International Conference on Development and Migration. The conference concluded with an announcement of the new “Rome Process” for addressing irregular migration. What exactly the Rome Process will mean for migrants remains to be seen. What it means politically, though, is already clear––the Far Right isn’t on the fringes anymore. On immigration especially, the nationalists are setting the tone.

Far Right Victories

Almost anywhere you look in Europe, the Far Right has something to celebrate:

- In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni hails from the most far-right party in power since the end of fascism.

- In Austria, the far-right Freedom party is polling as the most popular party in the country, with 28 percent support.

- In Finland, center-right prime minister Petteri Orpo came to power in June of this year in a coalition including the far-right Finns party. Orpo’s government didn’t waste any time getting embroiled in scandal, with his Finns party minister of economic affairs forced to resign just 10 days in over his light-hearted attitude toward Nazism.

- In Germany, the far-right Alternative for Germany party (AfD) is polling at 20 percent support, its highest point in its 10-year history. Only the Christian Democrats, the party of former chancellor Angela Merkel, are polling ahead of them at 27 percent support, while the party of current chancellor Olaf Scholz, the SPD, is polling behind the AfD with 18 percent support.

- In Sweden, the far-right Sweden Democrats came second in the 2022 general election with 20.5 percent of the vote, and supported the rise of the moderate coalition government in exchange for greater influence on policy.

- In France, the National Front of presidential runner-up Marine Le Pen is currently polling in second, in front of the third-place Renaissance party of President Macron.

- In the Netherlands, the far-right populist Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB), won the popular vote in provincial elections and 16 of 75 seats in the Dutch Senate this year, the first Senate election it contested since its founding in 2019.

And that’s just to name a few. Adding to the list, Poland and Hungary have been under the control of nationalist right-wing governments for years.

What’s Behind the Success

Covid-19, climate change initiatives, the culture wars, the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis, and inflation have all contributed to the Far Right’s recent success, with nativism at the heart of European far-right ideology. In all these cases––whether it’s a souring economic situation, limited state funds for welfare programs, or a changing culture––many voters believe immigration exacerbates the problem.

With irregular migration across the Mediterranean at its highest level in more than five years and the death toll rising, the public is demanding solutions. In 2021, before the recent increase in migrant arrivals, Europeans ranked immigration as the second-most important issue facing the EU, tied with climate change. According to a poll of Germans in December of 2022, 68 percent were concerned about the increase in the number of refugees arriving.

Mainstream political parties, meanwhile, have struggled to adapt. Many voters seem to demand limits on irregular migration, but liberal values, not to mention international law, compel European governments to welcome asylum seekers. That’s created a contradiction at the heart of EU policy: a stated willingness to welcome those fleeing persecution and hardship, and a private interest in dramatically curtailing the number of people that arrive seeking asylum. After once shunning the Far Right, mainstream European political parties are increasingly relying on its policies to address the migration dilemma.

Normalizing the Far Right on Migration

As early as 2015 the New York Times was reporting on how Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán’s immigration policies that European officials had decried as inhumane had “slowly been embraced by other European Union leaders, who vowed… at their final summit meeting of 2015, to ‘regain control’ of the Continent’s frontiers.”

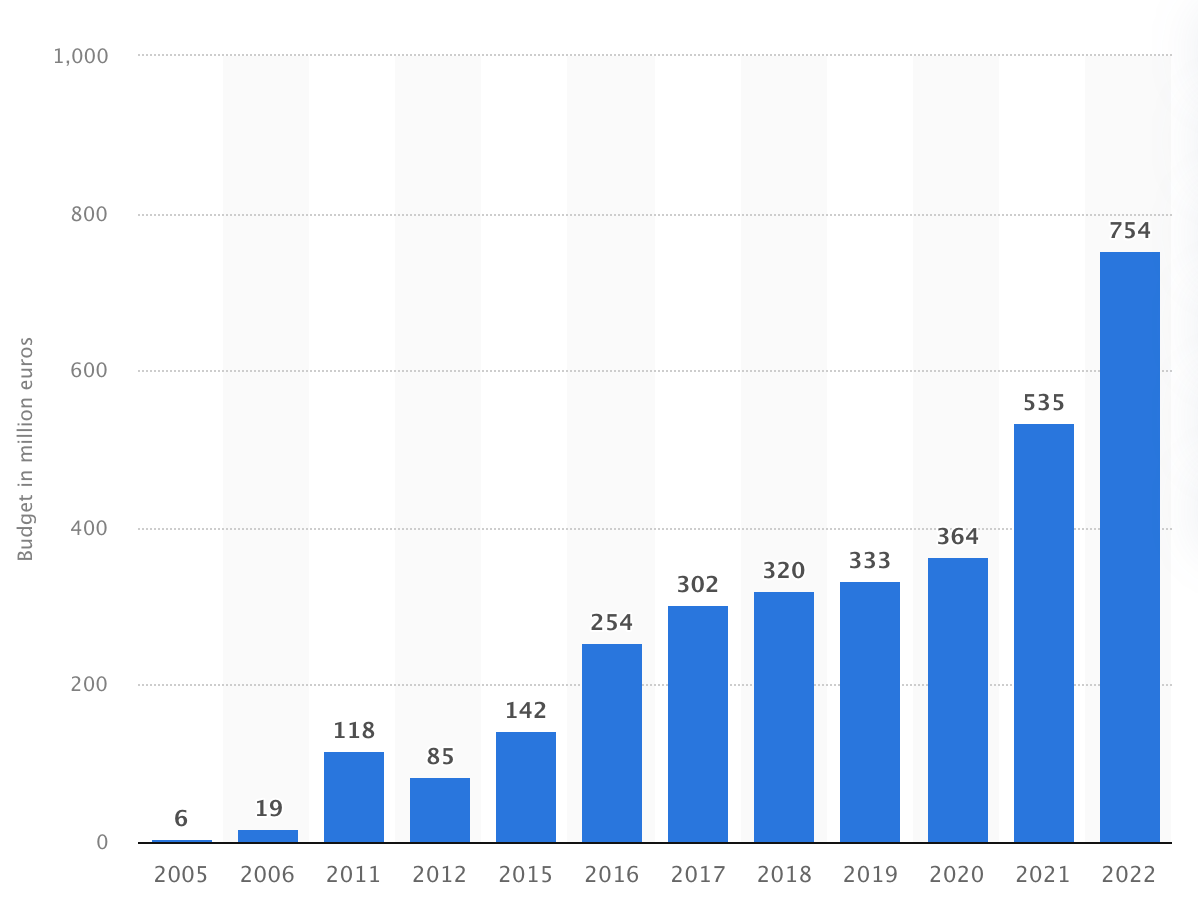

The commitment to limiting irregular migration has only increased since then, with the budget of Frontex, Europe’s border patrol, ballooning to $754 million in 2022 from $85 million a decade earlier.

All the while, once off-limits policies are now hitting the mainstream. In early 2017, the top EU official on foreign affairs, Federica Mogherini, offered not-so veiled criticism of Trump and his signature border wall by cautioning against “those who wish to build walls rather than bridges.” As late as 2021, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen doubled down amid some countries’ calls for border funding saying that “there is a longstanding view in the European Commission and in the European parliament that there will be no funding of barbed wire and walls.”

Then, amid a politically toxic increase in irregular migration, von der Leyen announced in February of this year that “[Europe] will act to strengthen our external borders” as EU heads of state endorsed a statement calling “to immediately mobilise substantial EU funds and means” for border defense.

EU funding for physical barriers is still technically off the table, but that could be changing too. In April the European Parliament passed an amendment for a bill that would allow EU funds to support a border wall. The bill ultimately failed, killing the amendment along with it, but the message is explicit: European positions on policing migration aren’t what they were a few years ago.

The normalization of the once-fringe Right has perhaps been most dramatic in the case of Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni. When Meloni came to power last September, pundits were fearing the worst and EU chief von der Leyen threatened consequences for Italy if it antagonized the EU.

Less than a year on, von der Leyen and Meloni traveled to Tunisia as two-thirds of “Team Europe” to finalize a migration deal with Tunisian president Kais Saied. According to that deal, the bloc would provide Tunisia more than €1 billion in aid in exchange for Tunisia policing migration more intensely. The turnabout has Politico proclaiming that “Italy has won migration.”

The Enduring Far Right

Over the last few years, the European center has moved further right on immigration, while the Far Right has become less euro-skeptic. Rather than trying to dismantle the EU, the Far Right is increasingly seeing it as a tool for restricting immigration and deepening a pan-European cultural identity. As Hans Kundnani, a research fellow at Chatham House, describes it, “the compromise between the center right and the far right is producing a kind of ‘pro-European’ version of far-right ideas and tropes, centered on the idea of a threatened European civilisation.”

The result is that the Far Right is unlikely to go anywhere. Even if these parties suffer defeat, their more popular ideas are rapidly integrating into the mainstream.

Speaking with Politico, a senior EU diplomat said “I think we are already seeing the Meloni effect… On migration, on climate, there has been a move towards the right, undoubtedly.”