How transnational repression extends authoritarians’ power into the free world

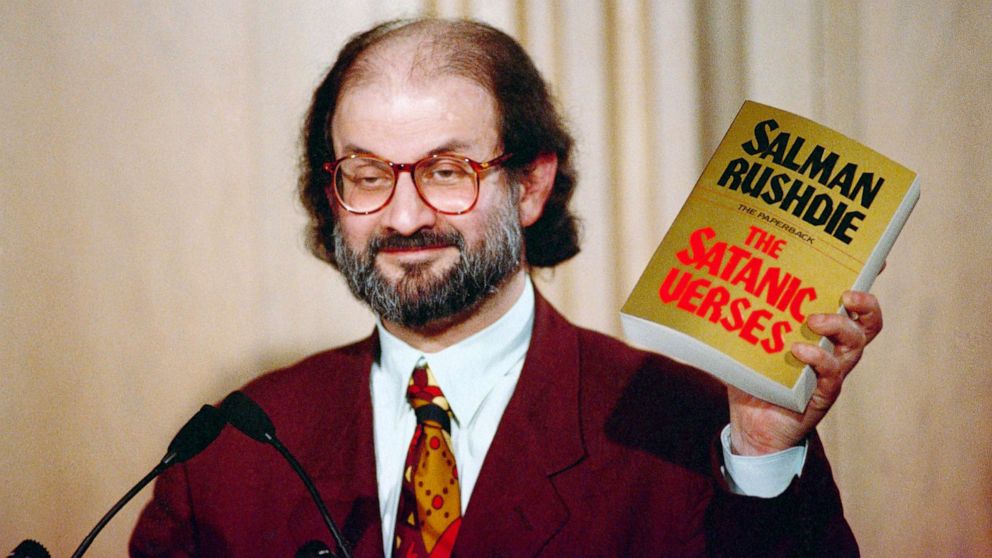

The attempted assassination of Salman Rushdie in quiet upstate New York last Friday was a shock. The fact that someone—anyone—got to him after thirty years of trying is tragically not.

Rushdie has a target on his head, placed by the Iranian regime, whose foreign ministry spokesman responded to the attack by saying, “We do not consider anyone other than [Rushdie] and his supporters worthy of blame or even condemnation.” “The devil turns blind,” read one headline in an Iranian newspaper. “Divine revenge,” another newspaper cheered.

Rushdie’s case is unique, but his experience facing the wrath of a foreign autocracy while living in the seemingly-sheltered safety of democracies is all too normal. Just among those associated with Rushdie, the terror wrought by the Iranian regime is remarkable, as ABC News recounts.

In 1991, Rushdie’s Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, was stabbed multiple times in Milan. Eight days later, Rushdie’s Japanese translator was found murdered in his office in Tokyo. In Istanbul in 1993, a mob set fire to the hotel of Aziz Nesin, a Turkish writer who reproduced sections from Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. Nesin made it out alive, but at least 37 died in the inferno. Four months later, Rushdie’s Norwegian publisher, William Nygaard, was shot three times outside of his home.

The attack on Salman Rushdie is the most recent high-profile case of transnational repression— the intimidation and targeting of dissidents living abroad by a hostile government. While Rushdie provoked the ire of Iran without ever having lived there, more commonly, critics of regimes are forced to flee their countries, only for the harassment they faced at home to follow them.

Take the case of journalist and RDI Freedom Fellow Masih Alinejad. While she was sitting on a call with RDI Chairman Garry Kasparov and Executive Director Uriel Epshtein last month, a man approached Masih’s house in Brooklyn, peered through her windows, and eventually returned to his car. Police pulled him over and found a loaded AK-47, multiple license plates, and one-hundred-dollar bills.

The Iranian regime is particularly brazen in its willingness to target dissidents, but it is hardly alone in surveilling, harassing, and killing critics throughout the free world. For far too many, freedom is out of reach even once they’ve made it to a democratic country.

How to Defend Dissidents

The US and EU are waking up to the threat of transnational repression, but their commitments don’t go far enough.

For an exhaustive discussion of the most important policies to defend dissidents, the recommendations from Freedom House’s expansive report on transnational repression, Defending Democracy in Exile, is a fantastic resource. As a starting point, though, the US should prioritize three things.

First, the US and other democracies must do more to protect dissidents from extradition back to the countries they were forced to flee. Authoritarian regimes abuse Interpol and its “Red Notices,” which essentially function as international arrest warrants imposed by one country and effective throughout all Interpol member nations.

Authoritarian regimes recognized that these Red Notices are often accepted without much scrutiny. In 2018, Natasha Bertrand wrote in the Atlantic about how Russia weaponized Red Notices in American courts and how the Department of Homeland Security frequently deferred to Russia in these instances. The US returned some actual criminals to Russia, but it has also detained dissidents subject to Red Notices for years as they fought their extradition in American courts. Famously, Bill Browder and RDI Freedom Fellow Enes Kanter Freedom have been targeted with Red Notices by Russia and Turkey respectively.

The TRAP Act of 2021 makes it so that the US cannot extradite someone merely because of an Interpol Red Notice, but it fails to challenge deficiencies at Interpol that enable it to act as a tool for anti-democratic oppression.

A few months after the US passed the TRAP Act, Interpol elected a new president, Ahmed Naser al-Raisi of the UAE. The UAE has a long history of stifling human rights and targeting dissidents, and Al-Raisi himself is implicated in international lawsuits regarding his involvement in torture within UAE prisons. Al-Raisi leads Interpol alongside officials from other countries notorious for targeting dissidents––a Chinese official on the executive committee and a senior official from Turkey. If the US really wants to do something to prevent the abuse of Interpol, it must use its leverage to ensure that the organization purportedly devoted to upholding the rule of law isn’t corrupted by officials from countries with no respect for it.

Second, the US must not allow Western technology to be weaponized against dissidents and democracy activists.

On a positive note, the US has limited sensitive tech exports to governments notorious for human rights abuses and private companies that have a history of selling spyware and surveillance technology to authoritarian regimes. Unfortunately, our efforts haven’t gone far enough.

American technology has been employed across the world to surveil and suppress protest movements. After the 2021 coup in Myanmar, the military junta quickly rolled out drones, hacking software and phone surveillance technology, much of it created in democratic countries, to stifle dissent and solidify their grip on power.

In addition to more aggressive export controls on sensitive materials, the US should pass the Foreign Advanced Technology Surveillance Accountability Act. As the bill’s authors explain, it would require us to study “the status of excessive surveillance and use of advanced technology to violate privacy and other fundamental human rights” every year. The government would have to focus on the abuses enabled by emerging technology, particularly that which we make ourselves, allowing us to respond to threats proactively rather than only after a serious incident.

And third, democracies must commit to challenging non-violent repression as strongly as they do kidnapping and murder. While physical violence is a particularly nefarious crime, it is also only one aspect of the constant monitoring, harassment and intimidation that dissidents face, particularly at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party.

While Iran and Russia command headlines for murdering prominent dissidents living in the free world, China is the country most active in targeting its critics. US official Uzra Zeya testified to Congress that China’s transnational repression is “the most sophisticated form of repression that exists in the world today. It is pervasive, it is pernicious, and it presents a threat to the values we hold dear as Americans and the integrity of the rules-based international order.”

Domestically, China has perfected the art of technological surveillance, integrating phone surveillance, advanced AI, and facial recognition software to monitor and police the Chinese people. Those efforts don’t stop at their nation’s borders, and Chinese nationals abroad are subject to widespread surveillance. Worse yet, networks of CCP officials and nationalists operate throughout democratic countries to intimidate Chinese dissidents and their supporters, often on college campuses. Security expert Anna Puglisi described Chinese efforts abroad as “an overall extension of the police state.”

The CCP has spent far more time developing these tools to monitor Chinese dissidents and activists than the US has spent responding. Countering these abuses must be a priority if we are to foster an environment where freedom of speech can truly flourish.

A World Safe for Democracy

That authoritarian regimes would go to such lengths to target dissidents abroad is a testament to dissidents’ power to effect change. Armed with only their voices, these dissidents can continue to make trouble for autocrats even from abroad.

But if free speech is dissidents’ greatest weapon, then it is also dictators’ greatest fear. Authoritarian regimes will do everything they can to silence people like Rushdie and Masih. It’s our responsibility to ensure that anyone in the United States, regardless of what government they might have angered, can live freely. If the US still aims to make a world safe for democracy, it should start at home.