Germany: September 26

(Photo: AFP)

Angela Merkel’s 16-year reign is ending, and Germany will elect a new government in September. The new chancellor will lead the most influential country in the European Union, manage Germany’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and mediate an increasingly fraught relationship with other Western democracies as Germany finalizes the Nord Stream 2 pipeline with Russia.

Still, the election is an encouraging one. Two candidates have a serious shot at winning, and both are defenders of liberal democratic norms. The likely victor, Armin Laschet, represents Merkel’s center-right Christian Democratic Union (C.D.U.). His strongest challenger, Annalena Baerbock leads the center-left Greens. Meanwhile, the far-right Alternative for Germany Party (A.f.D.) is polling in fifth at about 10% support, significantly worse than its peak of 17% in 2018.

What to watch for: a Laschet victory or a surprise from Baerbock

A Laschet victory is the most likely outcome (about 70% probability according to the betting markets), and his rule would largely be a continuation of Merkel’s. Like Merkel, he’s a moderate conservative and a strong proponent of the E.U., and supported the 2015 decision to welcome nearly a million Syrian refugees to Germany. Unfortunately, he falls into the C.D.U.’s perpetual folly of believing that Russian money is politically neutral and that it’s possible to line the pockets of Russian kleptocrats (err… “businessmen”) without weakening European security. Laschet would likely take a similar stance toward China; in 2019, he came out firmly in support of allowing Huawei, a Chinese tech company under the influence of the Chinese government, to build critical digital infrastructure across Europe that could enable state-run espionage and cyber attacks.

Annalena Baerbock of the Greens has long odds (16%, according to the same betting market), but still some of the best in the Greens’ 40-year history. One of the major reasons for their newfound competitiveness? A move towards the center. The Greens have worked hard in recent years to shed their label of being a Verbotspartei (“prohibition party,” in German) made up of hippies and pacifists. Their position on climate change has moderated, and their stance on authoritarian regimes like China and Russia is now hawkish.

The Greens see authoritarianism as one of the two most significant threats to the West (along with climate change), and think that the best way to protect liberal democracy in Germany is to pursue a policy of “dialogue and toughness” with Putin and Xi. So while a Baerbock government wouldn’t be cutting off trade or diplomatic relations with China and Russia, it would likely scrapthe Nord Stream 2 pipeline, step up pressure on Russia for its military buildup near Ukraine, and ban the imports of certain products from China in response to C.C.P. human rights violations in Xinjiang.

Whatever happens in September, German liberal democracy is likely to fare well. Laschet and Baerbock might differ on foreign policy, but both are ardent supporters of mainstream politics. The success of moderates like Laschet and Baerbock, and the A.f.D.’s failure to build on its surprisingly strong performance in the 2017 Bundestag election, shows that centrism and liberal democracy might be regaining ground in Germany.

Haiti: September 26 (1st round), November 21 (2nd round)

The Haitian presidential election was supposed to take place in October 2019, but President Jovenel Moïse pushed it to 2021 so he could serve a full five-year term. Of course, he was murdered last month, plunging the country even deeper into crisis with no end in sight. Moïse left Haiti without a functioning Parliament or Supreme Court and with two men simultaneously claiming to be Prime Minister. Even before Moïse’s assassination, Haiti was wracked by violent anti-government protests. Under this perfect storm, Haitians are supposed to choose a president.

What to watch for: protests or peace

Prime Minister and Acting President Ariel Henry, appointed by Moïse before his death but not officially inaugurated until July 19, has said that his priority is to proceed with the September elections. But this will be no easy task. The election is running behind schedule, the electoral council needs reform since Moïse politicized it, and Haiti’s major political parties––Moïse’s PHTK and the opposition, LAPEH––have not even announced their candidates for the presidency or Parliament.

If Haiti’s acting government can’t hold an election that the people see as free, fair, and representative, the nation may be fated to continue its downward spiral. A new president could bring much needed stability to the country, but could just as easily hasten its descent into anarchy. Without knowledge of who will even appear on the ballot, what will happen in Haiti is anyone’s guess.

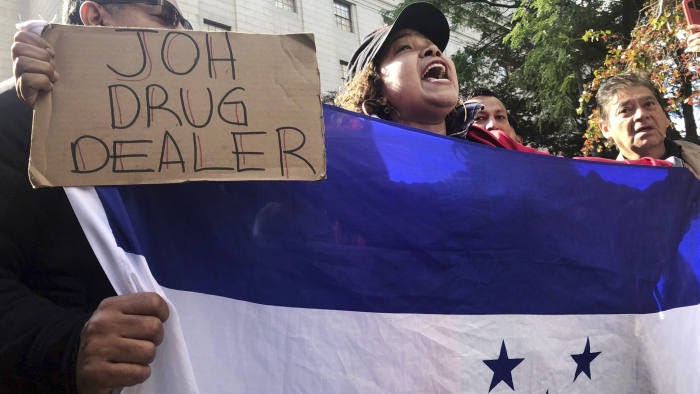

Honduras: November 28

Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández of the right-wing National Party is retiring, and the country will elect a new president on November 28.

The election comes as Honduras struggles with widespread corruption. Power and drug money go hand in hand in Honduras, and President Hernández is implicated in a series of drug trafficking charges. Some of those are tied to his brother, who was recently sentenced in a U.S. court to life in prison for smuggling an astounding 185,000 kilograms of cocaine into the country. Hernández’s successor on the National Party ticket, Nasry Asfura, embezzled $1.2 million while mayor of Honduras’ capital. Asfura’s main rival, Xiomara Castro, is married to former president Manuel Zelaya, who tried to illegally change the constitution in 2009 and was swiftly deposed in a coup. Also in the mix is Yani Rosenthal of the Liberal Party, an ex-convict for––you guessed it––drug-related corruption charges, who just finished serving three years in American prison.

What to watch for: an Asfura or Castro victory

The most likely outcome is a victory for Asfura, the ruling National Party’s nominee. He has a highly effective political machine at his disposal that will pull all the stops to get him elected, including, potentially, electoral fraud. It’s Asfura’s race to lose, and Hondurans can expect a continuation of the status quo. That would mean close ties with the U.S., moderate progress on economic development, and, in all likelihood, continued corruption and cartel influence.

Asfura’s best-positioned opponent is Xiomara Castro. Though not related to the more famous Castros of Cuba, her politics do resemble theirs. A socialist, she plans to change the constitution and move Honduras away from a free-market economy. While her supporters hope she could reduce poverty like her husband’s administration, her radical politics might instead condemn Honduras to more instability and dysfunction.

For Americans, neither option is a good one. The 2017 presidential election pitted the D.E.A. (investigating President Hernández’s family for drug trafficking) against the State Department (supporting Hernández because Zelaya, Castro’s husband, wanted to align with Venezuela, whose president has a $15 million bounty on his head). In 2017, the State Department got its wish: Honduras resisted aligning with Venezuela, but drugs kept coming to the U.S. November is a near repeat of the 2017 contest, and the result could also be the same. Without significant reform, Honduran drugs will keep going north, and Honduran citizens, fleeing violence and poverty, will probably do so as well. While it’s not clear if any candidate can bring stability to Honduras, an Asfura or Castro victory will portend different futures for the country: one where drug cartels could continue to run wild, and another where the country drifts toward Venezuelan-style radicalism. Whatever the result, America could very well be affected by the aftermath.